My journey in African space-making began in the 1960s, when as a graduate architect living under the strict regime of Apartheid South Africa, I began to challenge the era’s restrictive attitudes to space, which was exclusionary of the majority of the country’s population. Choosing to engage with rural indigenous African communities, I began to observe and document the ritual and daily practices of these cultures to gain a deeper understanding of how space represented their heritage, needs and aspirations, and shaped their world view.

This fieldwork formed a fundamental study documenting Southern African space-

making and its evolution during the latter half of the twentieth century. Much of the

research was done before Apartheid’s social engineering injustices dislocated

indigenous African communities from their customary way of life.

Although my learnings began sixty years ago, this inclusive approach to space

making is still relevant to designing and constructing responsible contemporary

African architecture that embraces diversity and a sense of identity and supports

sustainable development.

The parameters taken into consideration for green architecture to be successful

- Community consultation and involvement in the project as a prerequisite to the conceptual design

- Space-making that is congenial and enabling as to the building’s use and the cultures it is serving.

- Buildings that, in the true tradition of African architecture, were not about form, but the making of place, through incremental growth and adaptation to changing circumstances.

- It is not just the plan, but also the roof that generates an idea.

- An inherent order, scale, proportion, and regulating geometry that brings tranquility to the human experience of both indoor and outdoor special experiences.

- Symbolically timeless in revering both the past, the present, and the future.

- The provision of accessible, safe public space in a post-apartheid society

- A building process that is appropriate for the situation and has a low embodied energy.

- The importance of using locally sourced building materials and those with low embodied energy in component manufacture and the recycling in an urban context of waste and high embodied energy for components of reuse.

- The need for long-term low maintenance

- Participation of the community in the construction

- The project’s primary government funder stipulates that a certain percentage of the building contract work be completed by unemployed members of the local community, whose building skills training is part of their and the community’s empowerment.

Learning from and working with nature to create sustainable design

In 2005, my wife Diane, spotted an advertisement in a national newspaper to design a state-of-the-art interpretive center to house the priceless Mapungubwe artefacts and remains, including the world-famous Golden Rhino.

Situated at the confluence of the Limpopo and Shashe Rivers, the ancient Kingdom of Mapungubwe is now located in a SANParks game reserve that is part of a World Heritage landscape in South Africa. The southernmost African example of a 9th to 12th century civilization, which exhibited the social hierarchy of royalty occupying the high ground of a mesa top hill with the proletariat below through its raised topography, Mapungubwe was a symbol of Africa’s glory days. The profusion of gold, Ming and Malaysian pottery, and beadwork objects discovered at the site unmistakably demonstrated a civilization that traded and shared technical expertise with China, Malaysia, India, Persia, and Europe during the course of its three centuries of existence.

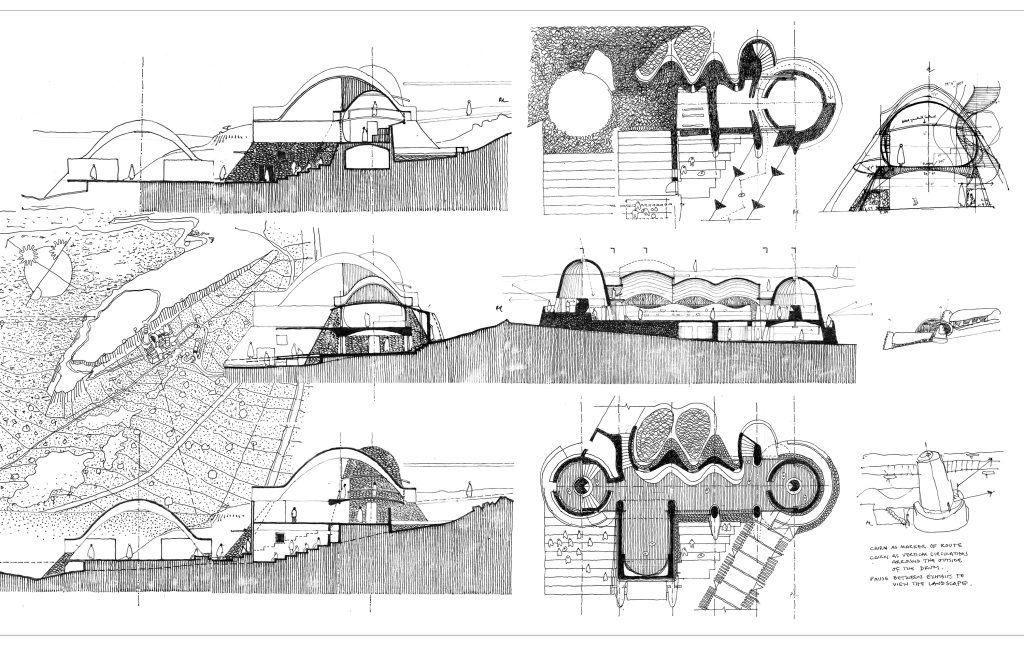

In designing the center, it was important to return to my studies in African space making and draw inspiration from the surrounding environment and reflect the cultural significance of the site. Furthermore it was learning from Nature and its intrinsic mathematical ordering, that was to become the inspiration for the design concept. What was to evolve was a cave-like architecture, a seamless continuation of the geology of the topography, and the biodiversity of the landscape while evoking a sense of the sacred in its darkness and ambiance.

The cave architectural expression and slatted light are the two main design elements of the interpretative center, which incorporates a zig-zag pilgrimage route with stone cairns demarcating the changes in movement and direction while traversing an eleven meter-high mountainside. When visiting the historical site, there were remnants of markers that formed a triangle, evidence of indigenous settlement courtyards, which is followed through in the geometry of the plan.

John Ochsendorf of MIT and Michael Ramage of Cambridge University UK (as former mentor /pupil), had learning from their research into Timbrel vaulting, become the advisors and engineers to the Mapungubwe Timbrel vaulting

Returning to the pre-industrial building technique of timbrel vaulting, compressed soil cement earth tiles are layered to construct the walls and roof of the building, in a catenary curve, picking up on the surrounding rock formations in harmony with the environment. What is notable about this technique, is that it works with nature’s forces to achieve large spans without the need for concrete or steel reinforcement. After the surface stones were cleared to facilitate the development on the site, they were used as cladding on the vaulted roofs and cairns. In using what the site provided, and not transporting in additional materials, we were able to reduce the carbon footprint by about 80%.

The challenge was to produce the earth cement tiles with the least amount of cement

possible while maintaining a minimum strength of 4 mpa. This was accomplished by

mixing the site’s soil with 5% cement content when making the tiles. We then had to

keep the tiles wet for seven days as part of a delayed drying process in order to

achieve the required strength.

What I haven’t mentioned is that each tile was hand pressed by members of the local

community, who experienced training in the production process and other building

skills, such as stone masonry, to foster employment and sustainable socio-economic

development in the area.

Responding sustainably to an urban setting

Considering the environment in an urban setting is just as important as in a natural

landscape for sustainable design. The Alexandra Heritage Centre is located in one of

the oldest townships of Johannesburg, South Africa. Believed to have been

established in 1913 by 40 families seeking work in the city, Alexandra is now a

multicultural home to 700,000. Most of the built environment consists of makeshift

dwellings, lacking in municipal infrastructure and continuously adapting to changing

conditions. The public realm is a dense web of street life, with alleyways branching

off into private living courtyards.

In 1942, Nelson Mandela rented a small room in ‘Alex’. In Long Walk to Freedom, he

writes: « Alexandra occupies a treasured place in my heart… It was the first place I

ever lived away from home.” Mandela’s room has since been proclaimed a national

monument, and the surrounding area, Mandela’s Yard, has been designated as a

heritage precinct. Opposite Mandela’s Yard, bridging across two street corners, is the

Alexandra Heritage Centre.

When I became involved in the design of the heritage centre, which was built in 2004,

my first inclination was to document the area surrounding Mandela’s Yard. By

measuring the entire heritage precinct, including all interiors, furniture, outdoor

spaces, and cars, I was able to gain insight into the existing context, as well as the

relevance of the organic evolutionary process that developed the township’s unique

character and urban grain, all of which fed into the design.

The aim of the site study was to achieve a balance between respect for the surrounding urban character, a small footprint to avoid demolition, and a monumental symbol. The concept of a bridge building that spans across 7th Avenue with blocks of accommodation and open courts frames the approach from the southern side, while the roof explores a familiar contrast with mono pitches that slope up and down. The building mass and site are drawn in a nearly continuous line, resulting in a seamless play of solid and void with the ground. The bridge has a colossal grandeur when viewed from afar but upon arrival, the structure dissolves into the sky, and the focus shifts to the urban aspect of the streets, with public squares flanking either side.

The idea of sustainability shifts in the tough urban environment, where the salvaged building materials and low maintenance costs contribute to energy saving. The Alexandra Heritage Centre’s steel framework was assembled quickly. In-fill panels of interlocking hand-pressed soil cement bricks have been used to define the walls of the center. Translucent polycarbonate sheeting on the bridge is lightweight, filters natural light and withstands the elements, requiring minimal maintenance. Salvaged building materials have been used to pave the public squares on street level.

The local community has been involved at the inception of the Alexandra Heritage

Centre. It was important to include their voices in the design decision-making

process. Job creation is a key factor in the centre’s function, from employing and

training artisans in the construction phase to empowering small business owners who

occupy the building. The design of the centre is tied to a much broader vision for

Alexandra, to bring about sustainable growth to the township.

The Alexandra Heritage Centre blends into the township’s vibrant urban fabric while

Mapungubwe learns from the surrounding natural landscape. Although these two

projects have very different settings, what ties them to an inclusive sustainable

architectural approach is that they both follow a design and build process that

sensitively responds to their environment and context, considering locally sourced

building materials while limiting energy consumption. Equally important is the

empowerment of the local communities, where each project aims to strengthen socio-

economic development for the long-term.

As we strive for a greener future in our industry, we need to remember that buildings in the true tradition of African architecture, were not about form, but the making of space, by adapting to changing circumstances while still revering cultural heritage and a sense of identity.

Peter Rich

Peter Rich Bio

Peter Rich is a Johannesburg based architect who attributes his learning to African space making as being central to his career. In 2009 he was awarded the World Building of the Year 2009 by the World Architecture Festival Barcelona for the Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre in Limpopo, South Africa. For his extensive African and global portfolio of built work, Peter has received numerous awards and prices. To name a few, he is the recipient of The UK Earth Award, the International Sustainable Architecture Award or The Wienerberger Brick Award. In 2013, he was shortlisted for the Aga Kahn Award. Peter further received the Gold Medal of Architecture from the South African Institute of Architecture for his contribution to African space making, and is an International Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects and an Honorary Fellow of the American Institute of Architecture. To add just one selected exhibition to the list, Peter’s work was displayed at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2018 as part of the Arsenale. In all of this, Peter finds time to teach and develop new curricula in Africa, India, Europe and the US. In his own words, “as an architect that specializes in community-based projects,” Peter would like to “share with students that architecture should have an inclusive approach, drawing on a community’s needs, aspirations and cultural heritage through social interaction in the design process, and working towards a ‘new urbanism’ that embraces both diversity and a sense of identity.”