Introduction

Sustainable development is defined as development methods and processes that do

not compromise the wellbeing of future generations. Questions around the concept of

sustainability and ecology directly relate to architecture and urban planning because

the construction industry currently accounts for 40% of greenhouse gas emissions

and 50% of global electricity demand. What’s more, human establishments are

increasingly urban, and, in the case of Africa, the population is exploding,

accelerating regional urbanisation processes.

Sustainable development is now a priority for international organisations,

associations, governments, building players and new city planners. In West Africa,

regional planning is marked by the construction of new “Smart Cities” that represent

the future: Eko Atlantic in Lagos, Sèmè City in Benin and Diamniadio and, more

recently, Akon City in Senegal. These cities also serve as communication tools to

attract international backers, galvanise the construction industry and, most

importantly, convey the image of an African urbanity of tomorrow. Based on Western

models and built of concrete, metal and glass, these city models barely take into

consideration the local climate and the specific urban features of African cities, let

alone our architectural heritage. Responses to infrastructure and resource needs

must be thought through to limit social and environmental degradation linked to

urbanisation; especially as cities have a long life, determine our quality of life and

economy, and should work towards the wellbeing of populations and the sustainable

management of natural resources. The Sahel and its subregion are endowed with an

immense wealth of urban and rural built, social and anthropological heritage – both

past and present – which holds the keys to construction and a modernity adapted to

our needs and realities. This study will therefore explore native cultural processes

and traditions, building the traditions and know-how of endogenous knowledge

systems on which these traditions and processes are based, to learn lessons that

can help define and promote sustainable design practices. ; It will also identify some

ideas and define areas of research and themes to explore for a potential exhibition

on the general theme: “Exploring cultural processes and aspects to define and

promote sustainable design practices in West and Sub-Saharan Africa”.

Traditional construction using earth and plant fibres

Traditional African construction is the result of the interaction of environmental

factors, such as the climate, vegetation and natural resources. West Africa is split

into two large climate zones: to the North is the Sahel running along the Sahara

desert, and to the South is a forest that runs along the Atlantic coast. Clay is

abundant in these two zones, and wood and plant fibres, such as bamboo and raffia,

are abundant in the forests and certain river banks. These local materials are mainly

used in traditional construction in West Africa.

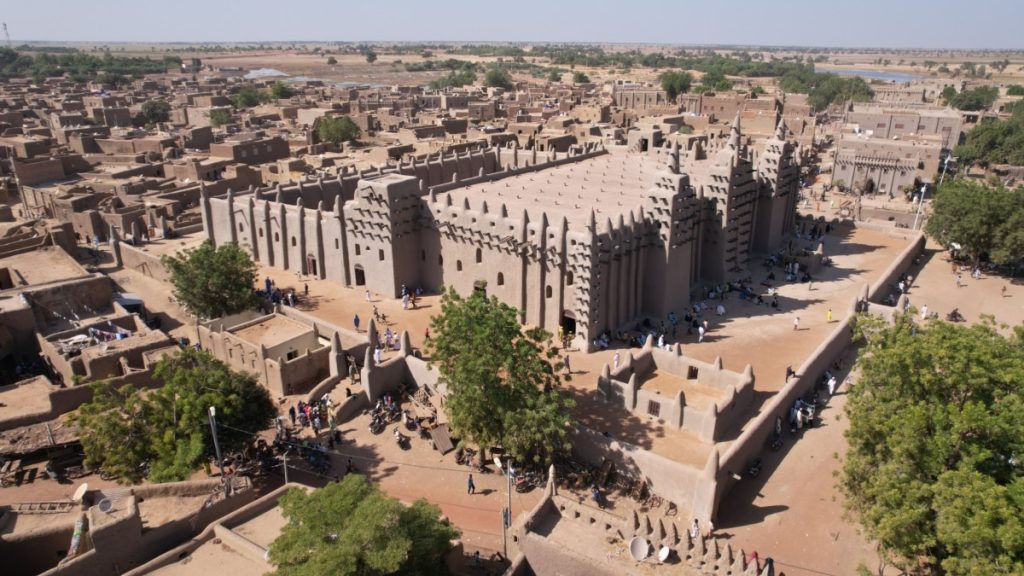

Earth structures tend to be detached houses, granaries, temples and mosques. Many

are old cities and buildings listed as UNESCO World Heritage because of the wealth

and diversity of earth construction techniques. The most famous sites include the

mosque and Old Towns of Djenné in Mali, the Batammariba houses in Togo and the

Cliff of Bandiagara, home to the Dogons. Like the majority of vernacular architecture,

these buildings use the materials available at the construction site and shape them

into a structure that is in keeping with the climate. Elements such as narrow windows

in the facades and verandas in front of houses are bioclimatic solutions boosting

shade and natural ventilation. In the Sahel, desertification is making plant fibres

scarce, and timber felling bans are increasing to preserve the ecosystem.

Nevertheless, earth remains the most sustainable material.

Built heritage and nature conservation

Traditional construction techniques are immaterial heritage that is disappearing due

to the movement of rural populations to cities and the saturation of the market with

concrete to build walls and sheet metal to build roofs. The loss of construction assets

leads to poorly constructed earth houses and thatched roofs, which are increasingly

seen as fragile and not resistant to rain and/or flooding. However, vernacular

architecture also integrated knowledge of cycles, and the maintenance of earth

buildings is an integral part of these structures. The wooden elements on the Djenné

mosque and plenty of similar structures serve as scaffolding. During an annual

festival, all the residents get together to replaster the mosque using clay from the

river before it floods during the rainy season. Integrating this knowledge of the

climate and cycles into the architecture and life of the building exemplifies a genuine

bioclimatic approach. What’s more, the collective aspect of maintenance work

enables knowledge sharing and unites populations around living heritage

conservation. Finally, the concept of cyclical time reminds us of the impermanence of

material things and that it is our responsibility to limit our intervention in a region to

maintain a balance with nature. African spirituality is holistic and “animist”, going

beyond attributing spirits to trees and stones. It defends the right to integrity of human

beings and natural elements alike. The wisdom of African societies lies in their

understanding of the interdependency between humans and nature because nature

is shared heritage that must remain accessible to all. One of the most striking

examples of this approach is one of the articles of the Kouroukan Fouga, which sets

out principles of conservation whereby any action by a human affecting nature must

be considered and guided: “Fakombè is nominated chief of hunters. He is

responsible for preserving the bush and its inhabitants for the happiness of all.”

“Before setting fire to the bush, don't look down at the ground, raise your head

towards the treetops.” One of the other moral lessons of African architecture is that it

has the interest of communities and individuals at its heart.

Between tradition and modernity

Although many such structures are old, 30% of housing in the region is still built using

traditional methods with walls of dried bricks, wooden framework and earth, thatch or

wooden roofs. Countries like Mali built modern cities in the 20th century, including

Mopti, which was built in the 1950s and laid out in a grid plan but with buildings made

of banco (earth). For most Africans, even those in urban settings, tradition is not

something remote because city dwellers come from traditional villages. This means

that even if they have no other experience of these structures, Africans can picture

the “earth hut of their grandparents”, which people recognise as a more comfortable

temperature than concrete houses. Several factors make people resistant to adopting

this material in urban environments, posing real cultural and structural issues. It is

therefore important to understand current trends in the building sector and push for

sustainable buildings in rural and urban environments alike, which will alleviate the

environmental impact of buildings through increased energy efficiency, more comfort

for residents and better resource management. This objective can be obtained by so-

called passive (bioclimatic architecture) or active (renewable energies) systems, both

of which have a way to go to be “cemented” in the minds of all the construction

players in West Africa.

Concrete, glass and air conditioning: markers of modernity

The postcolonial city is characterised by Western-inspired structures made of

concrete, stemming from acculturation processes that equate progress with Western

culture. Concrete and large windows now represent modernity even if they cause

thermal discomfort. The only recognised way to obtain thermal comfort in cities is by

installing air conditioning, which becomes a coveted item marking upward social

mobility. Through their production and use, concrete, excessive glazing and air

conditioning use a tremendous amount of energy, much of which is wasted, keeping

us dependent on fossil fuels. Passive architecture now offers a way of limiting energy

intake in building operations in a way that provides thermal comfort. In a Sahelian

and tropical context, the principles of passive architecture are based on buildings’

adaptation to the climate: orientate the building to limit sun exposure and boost

natural ventilation, ensure a supply of natural light, protect glazed windows and doors

from sun exposure, insulate roofs, etc. These principles are found in colonial and

post-independence structures from the international modernism movement, with

“tropical modernism” widely reflected in the subregion.

Renewable Energies

Running counter to passive architecture are active systems, such as solar panels and

wind turbines, two abundant sources of energy in West Africa with the potential to

help decrease our dependency on fossil fuels. In the building sector, photovoltaic

panels are gradually becoming more accessible. Residents often want to install them

to reduce their electricity bills. Although solar energy is a good renewable alternative,

dependency on solar batteries (which have a lifespan of around 5 years) should be

limited and accompanied by a passive building design that minimises energy needs.

Ideally, solar panels should not be used to power air conditioning because the energy

lost in this process goes against the savings principle that should guide the

sustainable development approach.

Although solar panels have limits in homes where energy use is higher at night, there

is high potential to power schools, offices and businesses using photovoltaic panels

with almost no batteries. These buildings could even overproduce energy and supply

electricity networks. In Senegal, for example, a law is currently being considered to

enable the resale of energy, which could motivate contractors to invest in solar

installations.

Players promoting construction using local materials

We are seeing a loss of knowledge and skills when it comes to earth construction

techniques in a context where concrete is flooding the market and can be bought

virtually anywhere. What’s more, many residents encounter difficulties finding

builders who are qualified in earth construction or have the skills to make thatched

roofs because there are fewer of them in the construction market, especially in urban

settings. Promoting and using traditional design techniques that are better adapted to

local conditions may help make construction accessible to everyone and support

local economies. Fortunately, a host of organisations and initiatives in the region offer

training and supervision in earth construction techniques.

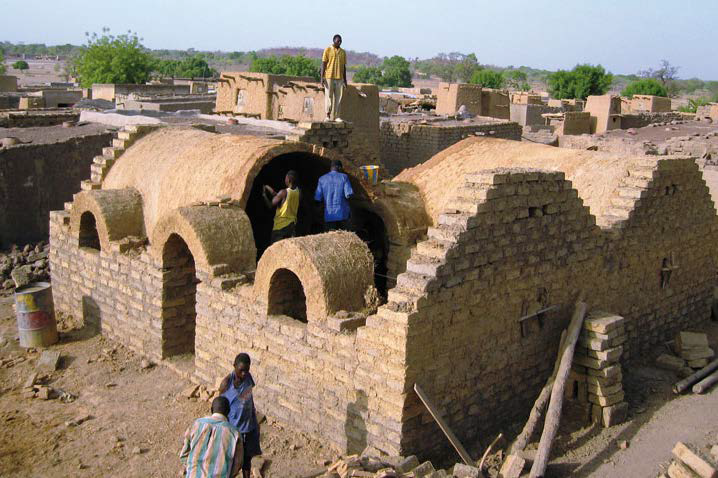

Voute Nubienne, an association located in Senegal, Burkina Faso, Benin, Ghana and

Mali, aims to “Train and support a green construction industry, stimulating the

employability of young people in rural areas”. Nubian vault is a building technique

from the Nile region of Africa that creates earth structures with vaulted roofs without

timber framework or shuttering. Thanks to its extensive network, the organisation can

put all the contractors wanting to build using this technique directly in contact with

skilled bricklayers. FACT Sahel+ also promotes earth construction through a network

of builders, bricklayers, architects, craftspeople, teachers, artists, students, civil

servants, engineers, urban planners, producers and entrepreneurs. They use a

participatory promotion and communication method and offer exhibitions, meetings,

debates, professional workshops, introductory workshops for children and adults,

competitions, research, experiments and digital and graphic tools. FACT Sahel+

recognises the best buildings in the subregion built using earth and plant fibres each

year with the Terra Award and Fibra Award. In addition to these two large

organisations, well-established construction companies in the subregion offer pre-

engineered earth construction materials that conform to national standards,

contributing to a renewed trust in earth among private individuals and property

developers.

In the field of earth block production, Elementerre in Senegal offer compressed earth blocks to build supportive elements from earth. They recently started producing earth-typha blocks, which provide excellent insulation, particularly for roofs. In Ghana, Hive Earth is leading the way in earth construction. They stand out for their use of the rammed earth technique, where earth is manually compressed in successive layers, giving the structures a distinctive texture. In Benin, Nature Brique makes terracotta from locally sourced clay, using nut and palm shells as fuel. Although terracotta blocks have a higher environmental impact than earth, the blocks produced are alveolar and thermally insulating, making them a better alternative to breeze blocks. Finally, South African firm Hydraform, famed for its production of housing using local materials after the Apartheid, is starting to promote the use of compressed earth blocks and the Moladi technology – using large earth-filled plastic panels – in West Africa. Hydraform provides hydraulic and manual presses to make interlocking compressed earth blocks to facilitate construction. The growth of earth construction companies means architects can dedicate themselves to designing earth structures, a growing number of which have been noted in West Africa. Senegal had Atelier Koé and, more recently, the Worofila collective, founded by architects who position themselves as specialists in bioclimatic design. Likewise, Architerre in Mali, run by Mariam Sy, is a design agency with an approach resolutely focused on sustainable development, designing architecture that contributes to comfort and wellbeing by limiting use and maintenance costs. In Niger, architect and researcher Moussa Abou stands out for his building technique – the Abou method – which eliminates wood and metal, materials he sees as unsustainable in the region, while Atelier Masomi, headed by architect Mariam Kamara, works to find innovative solutions for a sustainable future for communities. Since winning the Aga Khan Award for Architecture for the primary school in Gando, famous architect Francis Kéré has built several public buildings from earth. Similarly, star architect Sir David Adjaye undertakes institutional projects in earth using active bioclimatic technologies, such as the headquarters of the International Finance Corporation in Dakar, which combines earth blocks with a canopy of photovoltaic panels, making the building self-sufficient when it comes to energy. The region also features various projects using earth led by European architects. Dutch agency LEVS Architecten has a number of projects involving earth in the subregion and has led several social housing initiatives in earth in Mali and Mauritania. Finally, the CRAterre school continues to play a key role by making its experts available to train and support earth construction, renovation and training projects. Based in Grenoble, CRAterre is a world leader in earth-building vocational education and counts the founders of Architerre and Elementerre among its former students. It is not just earth. We are also seeing a resurgence of plant fibres as ecological materials for contemporary structures. In Nigeria, entrepreneur Ibrahim Salisu builds bamboo houses in central Kaduna. This entirely renewable material grows quickly, unlike some trees. The Nigerian authorities are considering bamboo houses, which can be built in two days, as a partial solution to the housing crisis. Finally, we should also highlight government initiatives in West Africa that campaign for more ecological structures, namely the National Programme for Energy Efficiency in Buildings (PNEEB) and the Typha Combustible Construction in West Africa (TYCCAO) programme under the Ministry of Environment in Senegal, which led to the construction of the Diamniadio ecopavilion and a school in Dagana from earth and typha. In Benin, the Ministry of Environment and Housing set up a “Community of manufacturers and installers of local construction materials” to promote local materials to political decision-makers. Although this last initiative is not hugely significant, it shows that African governments are starting to understand the economic benefits of promoting local materials. Slightly further afield, in Cameroon, the Local Material Promotion Authority(MIPROMALO), founded in 1990 under the Ministry of Scientific Research, serves as a central resource in the revival of construction using local materials. All the initiatives mentioned have great potential to be duplicated across Africa, where earth is widely available, and returns on investments in construction materials are short. Promoting and popularising building techniques and sectors using earth, typha and other geomaterials and bio-based materials will require extensive training and skills transfer programmes. To scale up these initiatives, a political desire at the state level is required to make this approach systematic and, above all, measure the environmental and economic impact of construction using earth and local materials on the local economy. Under the direction of Olivier Moles, CRAterre’s teams have created IMPEEC software, which measures the environmental and economic impact of different materials over their entire lifetime in a particular location. This type of tool may help authorities and contractors make informed decisions and gain a more global vision of the sustainability of different construction materials.

Finally, it is imperative to fund research at local institutions that are already working on these issues. The University of Thiès, the Centre of Architectural and Urban Research (CRAU) in Abidjan and architecture schools in Kumasi, Lomé and Abidjan must serve as laboratories and teaching grounds for built heritage and ancestral construction techniques to be used in contemporary and future buildings.

Earth: a luxury urban material

Although the majority of initiatives identified above are often in rural or peri-urban

environments where incomes are low, there is a growing trend to use earth in urban,

well-off environments, which may stop people from associating earth and straw with

ruralism and/or poverty. The Djollof hotel in Dakar and the Onomo hotels in Bamako

and Dakar are earth structures serving posh international clientele. What’s more, the

diaspora of the local African elite, who are inspiring a new globalised middle class,

are increasingly asking architects to build them earth houses with a modern aesthetic

that is a far cry from traditional earth mosques and huts. Although the elite can

influence the rest of the population to accept a new aesthetic, we should not fall into

a romantic aesthetic of earth, where we end up with buildings that look like they are

built of earth but are not and do not have the bioclimatic and economic benefits for

local industry. An elitist approach to ecological construction risks “greenwashing”,

where solar panels and earth plastering are enough to qualify your building as

environmentally friendly. The approach must remain sustainable, which means doing

everything possible to make construction a tool to promote local resources and

reduce dependency on imported materials.

Recycling and urban ecologies

African cities are places of creation where entrepreneurship is central to the economy

and the populations’ survival. For example, we are seeing economies created in

urban environments based on waste recycling. Several initiatives use plastic – an

environmental scourge – to create ecobricks: plastic bottles packed with non-

perishable waste. These ecobricks contribute to neighbourhood clean-up operations

while creating economic income for residents who sell the bricks to local authorities

who use them to build public buildings. Eco Brique Africa is an association leading a

number of initiatives in Senegal, especially in the Medina Gounass neighbourhood. In

Côte d’Ivoire, a UNICEF initiative supported by a Colombian organisation, Conceptos

Plásticos, is building classrooms from precast blocks made from plastic waste. They

aim to reduce the cost of a classroom for 50 pupils from 15,000 euros with standard

materials to 10,000 euros by using 5 tonnes of recycled waste.

Another example of an architectural application of the waste recycling economy is

broken tiles or offcuts from building sites that are resold for use as low-cost tiling for

outdoor courtyards and pavements. Although these initiatives prove the

environmental ingenuity of African city dwellers, they are limited because these

plastic blocks cannot be re-recycled in the long term. To be considered eco-friendly,

a building material must be sustainable for the entirety of its lifecycle, i.e. from the

extraction of the raw material through to its manufacturing process, transport,

storage, marketing, maintenance and recycling. All the energy used during this

process determines its carbon footprint, meaning plastics made from fossil fuels are

difficult to qualify as eco-friendly.

The African coastline and environment

The survival of the coastline is a significant issue in environmental discussions within

African cities. In Dakar in August last year, the inhabitants of certain communities

came together to denounce the monstrous construction projects along Dakar’s

Corniche. Of West Africa’s 15 (economic) capitals, 12 are on the Atlantic coast,

making them vulnerable to rising sea levels caused by climate change. Nigerian

architect Kunlé Adeyemi made coastal cities a key research issue by proposing,

among other things, a prototype for a floating school for Makoko, the floating slum in

Lagos that is suffering from rising tides caused by the new city of Eko-Atlantic, built

on the sea. The majority of indigenous groups in these capitals have a spiritual

relationship with water. Water spirits are seen as protective by the Ewe people of

Lomé, the Ga people of Accra, the Tchaman people of Abidjan and the Lebou people

of Dakar. The latter have a symbiotic relationship with water as they live off the fish

they catch. Rites to appease the spirits take place on the beaches of these capitals,

which are currently under attack from private investors. Traditional beliefs fear the

spirits’ wrath, and endogenous myths claim that disrupting marine ecosystems will

cause environmental disasters, such as the land being engulfed by the sea. Although

there are fewer and fewer expressions of traditional beliefs in multi-ethnic cities

influenced by imported religions such as Islam and Christianity, research on the

endogenous knowledge of indigenous peoples can provide more information on a

more symbiotic relationship with nature.

The concept of sustainability in African urbanity

Although the notion of vernacular architecture generally refers to old structures

mainly found in rural areas, vernacular culture refers to the cultural forms created and

organised by ordinary peoples in contrast to the high culture of an elite. African cities

also offer vernacular urban structures: modern family compounds, informal

establishments, spontaneous urban planning, etc. All these forms are made by the

people in the absence of formal adapted urban planning that corresponds to the

residents’ social norms and lifestyles. Cities are spaces of constant change and

transformation, and African cities highlight the collective intelligence that structures

spaces to meet the needs of the populations in real time. Local services found in

neighbourhoods, such as shops, phone boxes, vegetable sellers, car washes, coffee

sellers and maquis/tangana (traditional restaurants), are all social and economic

infrastructure that, to a certain extent, make African cities more functional. The

Western concept of the “smart city”, which accentuates an elite technoscientific

supremacy, could be adapted into a more collaborative and intuitive model in the so-

called “informal” African city. Via his fab lab, WoeLab, Togolese anthropologist and

architect Sénamé Koffi Agbodjinou advocates for using sharing technologies guided

by lessons learned from vernacular African societies and structures to build cities.

One of the principles – the fractal principle – supposes that the city can be created in

modular units, which have the unique characteristics of the city and can be multiplied

on a larger scale. He also advocates the Low High-Tech concept, defining a

vernacular and democratic architecture starting from local initiatives and

manufacturing based on what is available. To design sustainable African cities, we

must translate Africans’ consciences, cultures and lifestyles into the urban space by

relying on existing material and immaterial heritage. This production of the city must

also involve the possibility of enabling (supported) communities to shape their spaces

and leave space for new expressions of urbanity. New technologies also strengthen

sharing economies and enable greater information sharing. Small-scale urban

experiments, run by residents using local resources, hold the key to the cities of the

future.

Programmes such as Liaisons Urbaines have created a series of projects

highlighting public space in African cities via participatory experiences. Other similar

initiatives take the form of urban festivals, such as Partcours in Dakar and Chale

Wote in Accra. The strength of collective intelligence and action, like in old building

sites, enable people to express their identities in the space.

Conclusion

The architectural renewal resulting from knowledge of vernacular architecture

enables us to reconnect with our immediate ecosystem. The optimisation of regional

material and human resources must serve to create new, more equal societies that

put humans, their wellbeing and that of their community and environment back in the

centre of the space. African cities must be more liveable spaces for their residents

before being locations for property speculation. The concept of African sustainability

that has been shown in the past continues to be created in urban spaces. The choice

Africans make has the potential to serve the whole world in an era where extraction

economies and rampant capitalism have shown their limits.

References

African Cities Magazine, Resilient And Sustainable Cities Through Innovative

Solutions, 2021

Sename Koffi Agbodjinou, Afrotopiques: Cosmo-éthiques africaines et nouvelles

technologies pour Habiter la Terre en commun, 2020

Eyumane Baoule Assengone, Eléments pour une éthique africaine des

établissements humains, 2021

Armelle Choplin. Matière grise de l’urbain: la vie du ciment en Afrique, 2020

Construction 21, Le bâtiment durable en Afrique: enjeux, défis et réalités, 2015

Jean Dethier, Habiter la terre: L’art de bâtir en terre crue: traditions, modernité et

avenir, 2019

Crisna du Plessis, Sustainability and sustainable construction: the African context,

2001

Aurore Gros, Processus vernaculaires : L’architecture imprimée en 3D au service du

vernaculaire au XXI ème siècle, Master’s in Architecture dissertation, ENSAPB, 2018

Thierry Joffroy, Arnaud Misse, Robert Celaire, Lalaina Rakotomalala. Architecture

Bioclimatique et Efficacité Énergétique Des Bâtiments au Sénégal, 2017

Federico Monica, An African Way to Smart Cities, 2019

Thierno A. Ndiogou, Regards croisés sur la charte de Kurukan Fuga et la déclaration

universelle des droits de l’homme, 2016

Oliver, Paul and Hess, Janet B. African architecture, Encyclopedia Britannica, 2013,

Mbih Jerome Tosam, African Environmental Ethics and Sustainable Development,

2019

Odile Vandermeeren, FACT Sahel+ network, Construire en terre au Sahel

aujourd’hui, 2020

UNESCO, World Heritage Inventory of Earthen Architecture, 2012

Websites:

http://www.ateliermasomi.com/

http://www.a-architerre.com/atelier/architerre/

https://www.levs.nl/en/projects/social-housing-bamako

https://www.livinspaces.net/news/nige

https://moladi.com/plastic-formwork.htm

https://www.hydraform.com/

ria-to-adopt-48-hour-building-technology-using-bamboo/

https://www.globalconstructionreview.com/news/48-hour-bamboobungalow-

plan-launched-tackle-housi/

https://www.citedelarchitecture.fr/fr/video/actions-et-initiativesdu-

fact-le-reseau-des-experts-de-la-construction-en-terre-au-sahel

https://www.citedelarchitecture.fr/fr/article/liaisons-urbaines